Taking it Litterally. Daryl Lim Wei Jie’s 𝐴𝑛𝑦𝑡ℎ𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝐵𝑢𝑡 𝐻𝑢𝑚𝑎𝑛 as a Trash Course in Modern Civilization

From the very first page, which (un)welcomes the reader with a motto from Wang Xiaoni’s poem “A Rag’s Betrayal”—“now I’d like to pass myself off / as anything but human”—the lyrical persona in Daryl Lim’s poetry consistently, albeit teasingly, presents himself as a misanthropic prophet of humanity’s doom. Having spent thirty years in the belly of a capitalist whale, like the biblical Jonah, the Singaporean poet ventures into the Baudrillardian “desert of the real,” as suggested by the title of the volume’s first part. With “memories of betrayal” by rags and all else fermenting in his frustrated mind, as depicted in “The Prophet’s Day Out,” he foresees the coming garbage apocalypse to modern Sodoms and Gomorrahs, intonating his lyrical “Junkspace Rhapsodies”:

We’ve lost count of the subsidiaries we have

Money, they say, is its own reward

Your girlfriend would appreciate a new succulent

We’ve recently reached new heights of customer feedback

Money, they say, is its own reward

As he wanders through this “land of perpetual discount,” a place selling itself so cheaply as if sensing its imminent expiry and desperately trying to boost its revenue by a few pennies on its last day of validity (after all, “money is its own reward”), tenderness wells up in his heart. Thus, gradually, instead of impatiently awaiting the flood of trash or building a raft to survive the cataclysm alone, he embarks on a subtle world-saving mission through lyricism and humor. This mission, intended to lead to a “great reset,” forms the theme of the volume’s second part.

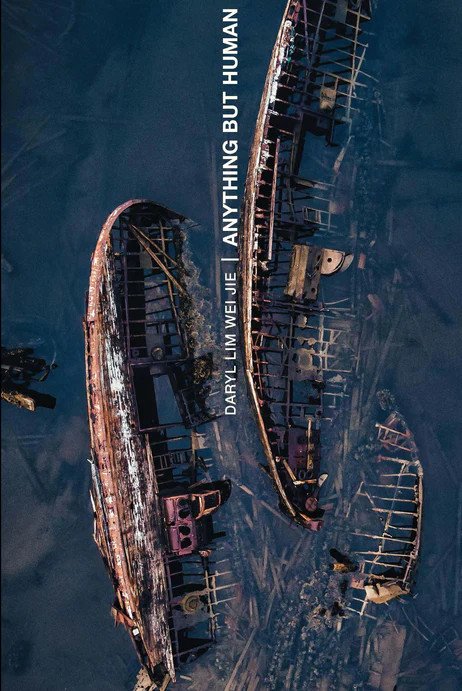

Daryl Lim Wei Jie, Anything But Human (Singapore: Landmark Books, 2021)

His task is a Sisyphean one. In an overwhelming reality best described by the title of the Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert film Everything Everywhere All at Once, he tirelessly collects whatever is still usable from the muddy blind alleys of development and buys nearly expired products from the lowest supermarket shelves. He packs his findings in seemingly provisional but finely woven and surprisingly capacious, flexible, and durable bags—his poems—and stores them in books. In his secret stash, tellingly, poetry lies “next to the alternative history of dry-cleaning.” Among the scavenger’s trophies, one can identify pitiful caricatures of great history, such as a “snowglobe of the Vietnam War” or one “of the Watergate Scandal,” remnants of grand architecture, including “makeshift Corinthian columns,” and once-great values, like “truth beauty beauty truth” chanted obsessively out of the tune in “Cloisters” in the “face of an unknown god.”

There are also shards of religious rituals and texts. For example, in “The Librarian,” lingering in the modern scriptorium with an Oreo wrapper as a bookmark, the speaker wonders: “What sets my announcements apart / from the Lord’s command to Abraham?” Moreover, “Fly Forgotten, as a Dream," the title of a series of seven poems in the collection, is a line from the Christian hymn “Our Lord, Our Help,” which the author learned as a child in a Methodist school. The liberated words, once falling into oblivion with dust gathering on their feathers, indeed start flying again on deplumed, emaciated wings—closer to earth, more like hens than angels delivering human prayers to the throne of God, but still. Beggars can’t be choosers. In a world “Where the Birds Don’t Lay Their Eggs,” and where “bird droppings / are currency,” every chicken counts. Though counting chickens is pointless because the universe is constantly on the verge of implosion under its own weight. Much like Lim’s dense verse.

In his “great reset” enterprise, the author finds support from an unlikely pen friend from another era: Tang-dynasty Chinese poet Bai Juyi. Bai’s works, in Lim’s experimental translations from classical Chinese, are scattered across the second part of the collection, with extensive blanks between words and unconventional line divisions, as if exploded by the bulging undercurrent of silence about which he writes in “Narrative (VI)”: “I have let the silence well up for years / and now it flavours everything.” These translations were first published in Exchanges: Journal of Literary Translation, accompanied by letters addressed to “Mr. Bai,” where Lim tells Bai Juyi of how he encountered and fell in love with his poetry during a trip to Xi’an. He also discusses other premodern Chinese poets, contemporary Sinophone poetry scenes worldwide, practical and philosophical aspects of translation, and the multiculturalism of ancient and modern China. Unable to reach the addressee, he responds himself using excerpts from classical texts, including Bai Juyi’s letters to friends.

In Anything but Human, rather than speaking to Bai, Lim speaks through him. Incorporating the works of an ancient poet into his own literary project, he signals that he identifies, at least to a certain extent, with his great predecessor, sharing his yearning for a more peaceful life in communion with nature. Bai’s poetics permeates Lim’s writing, helping him reset his own voice to a more pensive and quieter tune. “This much talk has made me hungrier / than a tick on a teddy bear,” he confesses disarmingly in “Narrative (VIII),” before proceeding to compose a “New World Symphony.” This is soon complemented by a new “Credo” and the anticipation of “a new calendar” with “the months named after / nerve agents” in the “Age of Miracles,” which closes the book.

Happy ending? Well, not exactly. That would be too beautiful to be true—and too boring to be poetry. Rather, it marks the beginning of a new adventure. Lim, undoubtedly one of the most original and intellectually restless rising Asian authors, will certainly invite us on this journey in his next collections. In Anything but Human, as we learn from the final poem, his unruly excursions beyond the limits of common sense, good manners, and social convention have earned him a more severe punishment than the proverbial slap on the wrist: “the light shaved ten pounds / off [his] wrist.” Despite this harsh pushback, he remains undeterred. I’m sure he will continue to surprise us with fascinating, uncompromised observations and revelations about the world and ourselves, both as humankind and as individuals.

Joanna Krenz is a scholar and translator of Chinese literature. Her research interests include modern poetry in intertextual and interdisciplinary contexts, especially its interactions with natural sciences. She is the author of the monograph In Search of Singularity: Poetry in Poland and China Since 1989 (Leiden: Brill, 2022), and the translator of nine books, most recently the Polish rendition of Yan Lianke’s novel Heart Sutra (心经, PL Sutra Serca). She works as an assistant professor at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland.