TSLR Online Collection

Browse all TSLR Online articles by category.

Remembering Maung Hmek aka Shwe Yoe aka James C. Scott (1936-2024)

Burmese poet ko ko thett remembers James C. Scott, Sterling Professor of Political Science and Professor of Anthropology at Yale University. Professor Scott was a comparative scholar of agrarian and non-state societies, subaltern politics, anarchism, and high modernism. He also helped to revive the Independent Journal of Burmese Scholarship.

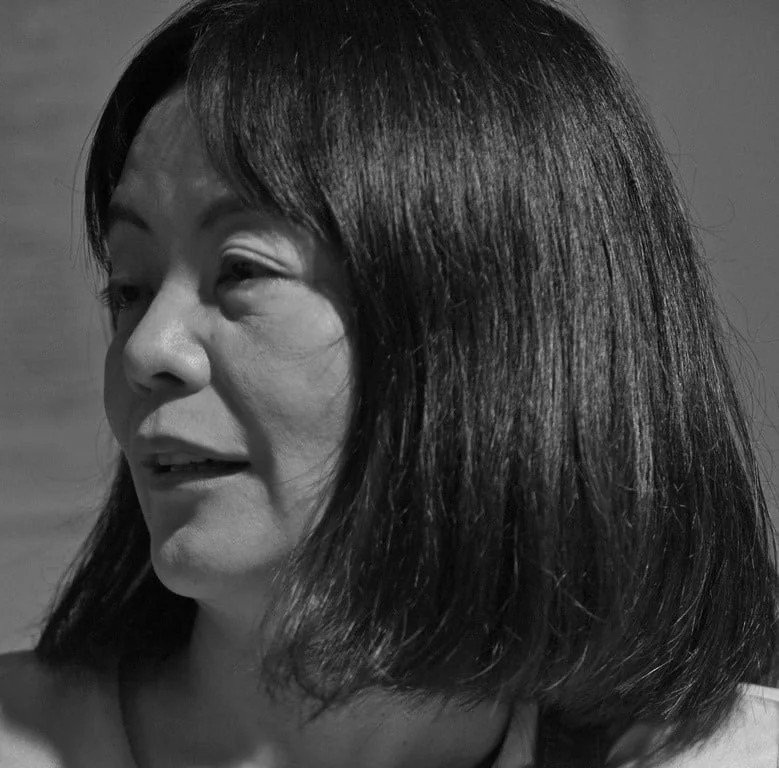

“Language is always there in front of me.” An Interview with Yoko Tawada

“Languages never have to die. People can forget them, but they do not die. Language is not organic. The important thing is that we perceive it as organic. Language can also express male and female genders on different levels, but language itself is neither male nor female, which is a great liberation for me.”

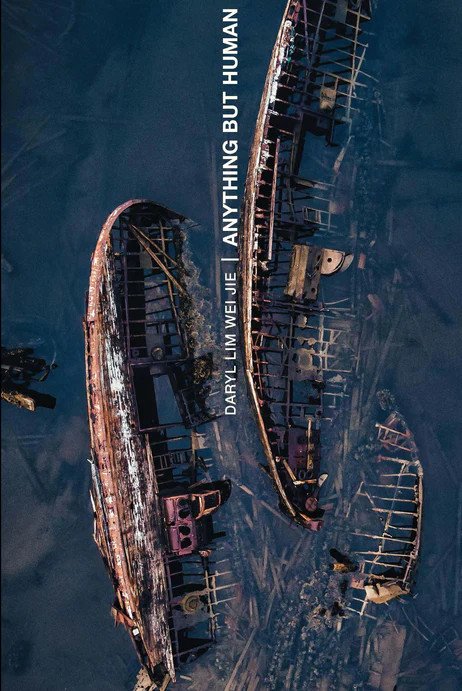

Taking it Litterally. Daryl Lim Wei Jie’s 𝐴𝑛𝑦𝑡ℎ𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝐵𝑢𝑡 𝐻𝑢𝑚𝑎𝑛 as a Trash Course in Modern Civilization

Scholar and translator Joanna Krenz reviews Singaporean poet Daryl Lim Wei Jie’s poetry collection Anything But Human (2021).

The Man Who Would Become Orwell. On Paul Theroux’s Novel 𝐵𝑢𝑟𝑚𝑎 𝑆𝑎ℎ𝑖𝑏

Eric Arthur Blair, the 19-year-old Eaton graduate who would become George Orwell, arrived in Burma (Myanmar) in 1922. For the next five years, he worked his way up the Imperial Police hierarchy, eventually becoming an assistant police superintendent. His posts took him to towns and villages infested with mosquitos, brothels, nationalists, thieves, and roaming armed gangs.

The Road to Nowhere or the Path to Peace?

By Omer Bartov, Samuel Pisar Professor of Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Brown University

Editor’s Note: Omer Bartov's essay will appear in the next issue of TSLR, scheduled for publication in Spring, 2024. This next issue features two new elements: first, it will be the journal’s first themed issue, with the theme being the concept of Flux; and, second, it will include a new section on Criticism, featuring non-fictional essays on timely topics. Omer Bartov’s essay is one of four pieces that will appear in the next issue’s Criticism section, but given the unusual timeliness of its subject matter, we are pre-publishing the essay here. - Carlos Rojas (Duke)

We are currently living through a period of unprecedented chaos and confusion in the Middle East. As some have predicted, there are signs that the turmoil is spreading ever wider. Yet no formulas have as yet been proposed as to how to put the genie back in the bottle. Violence, strife, and war have a logic of their own. Without conceptualizing concrete political goals, they will keep expanding, feeding on the rage, sacrifice, and vengeance they produce, until at least one of the parties is either exhausted or wiped out.

The situation of flux in which we find ourselves at the moment in the Middle East is just one component of a general sense of confusion and uncertainty in the world, rooted in various factors ranging from economic uncertainly, distrust of political leadership, massive displacement of populations, the long-term effects of the Covid-19 epidemic, and the ongoing climate crisis.

In the face of such an array of threats and fears, one is tempted to simply withdraw into the private sphere, shut out the news, and engage as best one can with the pleasures, or at least the more manageable affairs of daily life. The problem with this choice is that—just as in the case of avoiding political speech on, say, university campuses, for fear of being immediately labeled as supporting one camp or another—it creates a vacuum, which tends to be swiftly filled by the extreme voices. In other words, silence, unclarity, confusion, and passivity themselves generate polarization, whose outcome is ever more strife and violence.